Hannah Williams (Queen Mary University of London)

One of the key collaborative activities of our 2024 program for the Colonial Networks project were two workshops we ran at NYU’s Center for the Humanities on November 8, 2024. This post is about the workshop we titled Unsettling Collections: The Paris Art World and Haiti/Saint-Domingue, which brought together a group of museum curators, scholars, auction house specialists, and collections researchers to imagine new ways of telling stories about French art through digital approaches to provenance histories.

The other workshop we ran that day was titled Critical Counter-Mapping Black Geographies of Art in Haiti/Saint-Domingue, and we’ve written about that in a separate note.

Unsettling Collections

The idea for “unsettling collections” came out of the branch of our project focused on Connecting Paris & Haiti/Saint-Domingue, which explores the profound links between members of the eighteenth-century Paris art world and their colonial activities in Haiti/Saint-Domingue. One of the main components we’ve been researching is plantation owners and colonial administrators who are now better known (among French art historians, at least) as important French art collectors, among them the comte de Vaudreuil (1740-1817), Jean-Joseph de Laborde (1724-1794), and members of the extended Choiseul family. We’re comparatively mapping the properties these people owned in Paris and in Haiti/Saint-Domingue, researching their activities as enslavers and the wealth they generated from colonial commerce, and tracing the vast number of artworks from their collections that, owing in part to the upheavals of the French and Haitian Revolutions, ended up in public museums throughout Europe and the U.S. The screenshot below is a slide that visually summarizes the material intersections of this research into people, property, and objects.

One result of this research is a growing dataset of eighteenth-century French artworks which are—as a result of their provenance stories—directly or indirectly implicated in the disturbing colonial histories of Haiti/Saint-Domingue. As much as this research “unsettles” the histories of these eighteenth-century Parisian art collections, it also provides an opportunity to productively disrupt and reorient the current museum collections in which these objects now reside.

That was the objective behind the Unsettling Collections workshop: exploring with curators how we can tell new stories and engage new audiences through reimagined approaches to provenance – and vitally – how digital spaces and opportunities might address some of the many challenges posed by such an endeavor.

The Workshop: Conversations and Thoughts

We invited a group of curators and collections researchers, all of whom either work in museums that currently hold objects from our dataset, or who work with colonial provenance in some way. We’re extremely grateful to these colleagues for generously sharing their time, expertise, and creativity to come together and exchange ideas: Taylor Alessio (Christie’s); Esther Bell (Clark Art Institute); Marie-Laure Buku Pongo (The Frick Collection); Laura Sofia Hernandez Gonzalez (Museo de Arte de Ponce); Yuriko Jackall (Detroit Institute of Art); Elyse Nelson (Metropolitan Museum of Art); Guillaume Nicoud (Archivio del Moderno, Università della Svizzera Italiana); Christy Pichichero (George Mason University); David Pullins (Metropolitan Museum of Art); and Perrin Stein (Metropolitan Museum of Art). The other workshop participants were ourselves (Meredith Martin and Hannah Williams) and members of our NYU-based project team: Lucy Appert, Selin Ozulkulu, and Zhiyang Wang.

Collectively, the provenance histories of the artworks in our dataset reveal crucial insights into connections among the French metropolitan art world, colonial economies, and enslavement in the eighteenth century. But these are often difficult to stories to tell within the gallery, or even within a single institution.

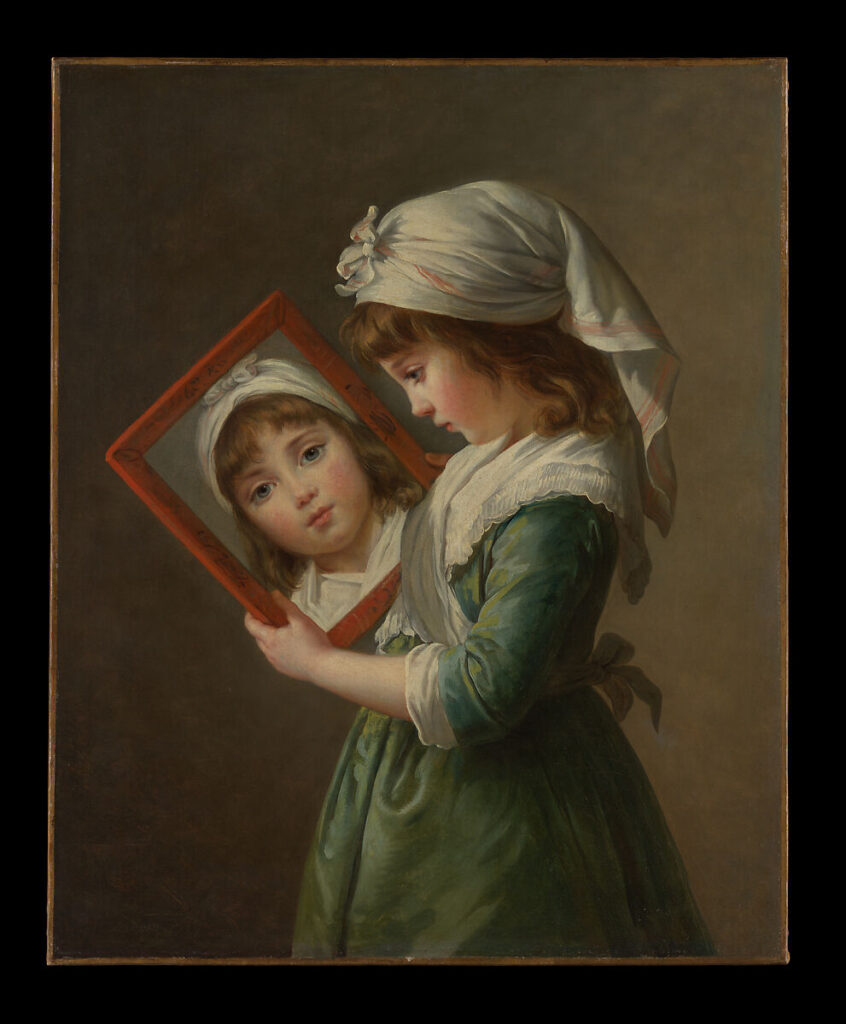

Within the gallery, provenance stories aren’t always the most pertinent details to foreground in the restricted modes of in-gallery interpretation available. For example, the comte de Vaudreuil owned two paintings that are now in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York: Elisabeth Vigée Le Brun’s Julie looking in a Mirror of 1787 and Bartholomeus Breenbergh’s Preaching of John the Baptist of 1634. Vaudreuil was friends with Vigée Le Brun, and the two (along with Vigée Le Brun’s art dealer husband) were key figures in what we’re calling the “colonial networks” of the Paris art world. So in the case of the Met’s Vigée Le Brun painting, its provenance connections to Vaudreuil and his enslaving activities, which formed the basis for his wealth, would be a highly relevant detail for inclusion in a wall label, providing a crucial aspect of its history for museum visitors. But it’s quite different in the case of the Breenbergh painting. For this seventeenth-century religious landscape by a Dutch artist, which wasn’t acquired by Vaudreuil until over a century after it was made, this episode or “event” from its longer provenance history is not the most relevant detail to include on a wall label for contemporary museum visitors.

These complex stories are also difficult to tell within a single institution, not least due to the vast dispersal of these objects after they left their eighteenth-century collections. Vaudreuil’s artworks, for instance, are now held in scores of museums around the world, including the Met in New York, the National Galleries of Art in London and in Washington, D.C., the Wallace Collection in London, the Musée du Louvre in Paris, and the Museo de Arte de Ponce in Puerto Rico (to name but a few).

Digital approaches can provide scope for overcoming these kinds of challenges, and that was the focus of our conversations in the workshop. We discussed the role that provenance—typically presented as a dry, highly systematized list of names whose stories and significance are not evident to most readers—plays in different kinds of museum interpretation (from the wall label to the museum website), and we considered examples of objects with provenances tied to French histories of colonialism and enslavement and how these links are currently communicated (or not). Throughout the workshop, lots of valuable comments and ideas were raised about the needs and interests of different audiences, the political pressures that museums face, and the vast potential of museum websites and social media channels as a space to animate provenance and, in so doing, to complicate and enrich the lives of objects.

Building on these valuable and on-going conversations with curators, we are currently working with our digital team to prototype one approach to animating provenance in this way, working with some key objects that have emerged from our research.

Cite this post as: Hannah Williams, “Unsettling Collections: A Workshop with Museum Curators and Collections Researchers,” Colonial Networks (January 2025), www.colonialnetworks.org