Meredith Martin (New York University)

Collaboration and conversation are central to our Colonial Networks project. On November 8, 2024, we hosted two workshops at NYU’s Center for the Humanities to discuss, critique, and generate new ideas for two project components that we are currently developing. One of these workshops, which Hannah Williams has written about in a separate post, considered how to “unsettle” museum collections and tell new stories about art objects through digital and decolonial approaches to provenance. In the other workshop—discussed here—we explored how to use critical counter-mapping as a tool for 1) subverting dominant narratives of colonial maps of Haiti/Saint-Domingue; and 2) re-ontologizing these maps with stories of Black life and resistance.

We’re grateful that our colleague Christy Pichichero (George Mason University), a leading scholar of French history and Black studies who has led efforts to promote diversity, inclusion, and anti-racism across the humanities, offered to co-organize and run the session with us.

The Silencing of Colonial Maps

The Colonial Networks project grew out of our desire to “map” and examine largely unknown connections between Haiti/Saint-Domingue and the Paris art world during the late 18th and early 19th Centuries. Our starting point for analyzing these connections were late 18th C. colonial property maps of Saint-Domingue, among them René Phelipeau’s plan of the area around the town of Cap-Français (Cap-Haïtien) shown below. The land depicted on this map is divided up into plantation boundaries, all of them bearing the names of mostly white absentee planters, which together read like a “who’s who” of the Paris art world, with the names of major collectors, patrons, dealers, and even artists and architects represented.

Maps like Phelipeau’s, on the one hand, reveal the profound, disturbing links between land ownership and enslavement in Saint-Domingue and the production and consumption of art in the French metropole. But they also occlude the stories of generations of Black men and women who lived, loved, and labored in these spaces and resisted the oppression and erasure they imposed. We want to create an alternative, layered version of this map that acknowledges (following Haitian historian Michel-Rolph Trouillot) its “silencing” of the past while also aiming to center Black and Indigenous geographies and restore some sense of the human and ecological devastation it embodies. While other components of the Colonial Networks project consider how the exploitation of human beings and natural resources in Haiti/Saint-Domingue fueled the growth of the Paris art world, this part of the project focuses on the vibrant visual and material culture of Haiti itself, notably via stories of the many enslaved and free artisans and laborers who played a vital role.

The Workshop: Conversations on Counter-Mapping

Since we (Hannah and I) are not specialists in Caribbean or Haitian history, Black studies, or Black digital humanities, we were very aware of the need to learn from other scholars who have been doing innovative work in these areas. We also wanted to hear from map specialists about the creation and agendas of colonial property maps and from musicologists about how one might reanimate lives and stories through sound. Along with Christy Pichichero, we were honored that so many scholars whose work has inspired our own joined us for this workshop, and we are grateful for their time and input: Arielle Alterwaite (University of Pennsylvania), Marlene Daut (Yale University), Julia Doe (Columbia University), Dani Ezor (Kenyon College), Alex Gil Fuentes (Yale), Jessica Marie Johnson (Johns Hopkins University), Bertie Mandelblatt (John Carter Brown Library), Siobhan Mei (University of Massachusetts Amherst), David Pullins (Metropolitan Museum of Art), and Cloe Gentile Reyes (NYU). We were also joined by members of our NYU-based project team: Lucy Appert, Selin Ozulkulu, and Zhiyang Wang.

Christy started us off with an overview of the field of critical cartography, beginning with Brian Harley’s 1988 essay “Maps, Knowledge, and Power,” whose foundational insights continue to resonate:

Harley’s observation that European maps actively promoted territorial appropriation and dispossession certainly pertains to the plan by Phelipeau, whose trompe l’oeil frame suggests it could have been hung in a Parisian townhouse and used to flaunt territorial claims by absentee planters. It is biased both in foregrounding the names of mostly French landowners and colonial districts and in suggesting a neat, orderly parceling of space where agricultural exploitation and human habitation is minimized. The presence of the many thousands of enslaved African and Afro-descended laborers who lived on these properties, for instance, is alluded to only by tiny squares denoting slave cabins in neat rows.

The individual lives, struggles, relations, and resistance of these enslaved individuals, who often charted their own counter-geographies and traversed property boundaries in order to share knowledge, build community, and fight oppression, are completely absent. Inspired by the work of several scholars, among them John Garrigus and Catherine MacKittrick, as well as digital humanities projects led and supported by some of our workshop participants (notably Alex Gil Fuentes and Jessica Johnson), we discussed how one might bring these Black lives and geographies to the forefront.

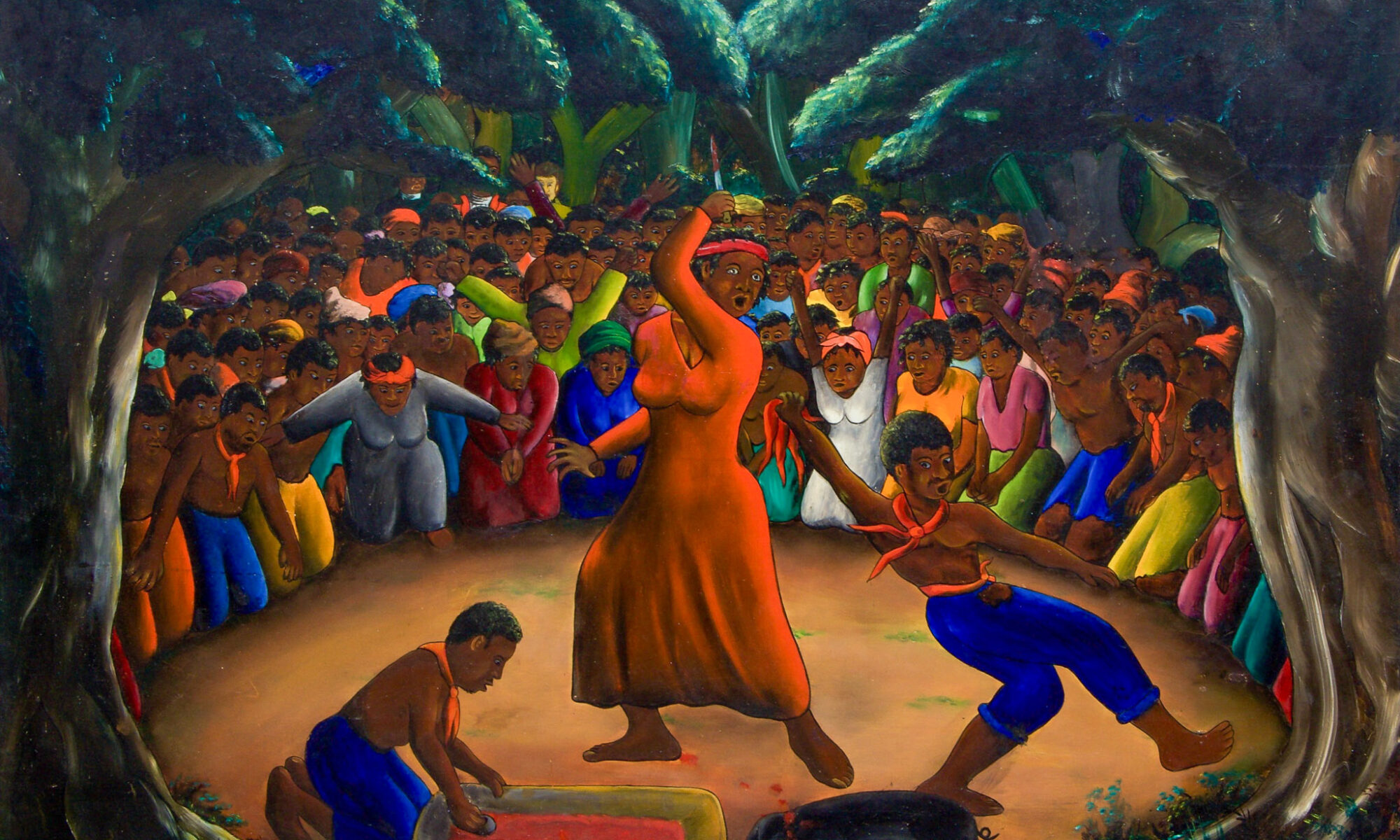

One approach we considered was to feature the work of modern Haitian and Caribbean diasporic artists who reimagine the past by portraying historical events for which we have no surviving visual record. For example: by honing in on just one small slice of our property map, like the detail shown above, we can see plantations “belonging” to such noted Parisian art world figures as Vaudreuil, Choiseul, and the comte de Vergennes. But one could tell a different story by indicating that this was the same territory where Toussaint Louverture was born and lived (on the Breda plantation); where the Bois-Caïman ceremony, a key event precipitating the Haitian Revolution, took place; and where the Battle of Vertières, a decisive turning point in the struggle for Haitian independence, was fought. Many artists have visualized these figures and events, from the 20th C. Haitian painter Jacques-Richard Chéry to the contemporary artist Raphaël Barontini, whose 2023-24 installation at the Paris Panthéon, together with a related exhibition entitled Dare Freedom, filled in important gaps in the Panthéon’s selective vision of Revolutionary liberty.

Our workshop participants had a range of responses to the cartographic, visual, and archival material we presented. (“I hate that map!” was one of the first ice-breaking responses.) They also had helpful suggestions on how to engage public and community audiences beyond art history, and to bring in Black and Indigenous perspectives. We discussed the importance of forging a dialogue with scholars and stakeholders in Haiti, and of thinking about how our project relates to Haiti’s ongoing crisis today. We aren’t sure what our critical counter-map will ultimately look like. It might resemble a pilot project created in Fall 2024 with graduate students from NYU’s Institute of Fine Arts, although we may use a different format as well as animation and sound elements. But as one of our participants noted at the end of the session, the only way forward is to start doing the work, to acknowledge self-doubts and limitations, and to welcome advice and help when it’s offered.

Cite this post as: Meredith Martin, “Black Geographies of Art in Haiti/Saint-Domingue: A Workshop on Critical Counter Maps and Digital Humanities,” Colonial Networks (February 2025), www.colonialnetworks.org